Judges and Witnesses

In the presence of Laetitia Dosch, Jean-Stéphane Bron, and Stéphane Demoustier, filmmakers; Antoine Reinartz, actor; Nathalie Hertzberg, screenwriter; and Jean-Baptiste Thoret, writer and film historian

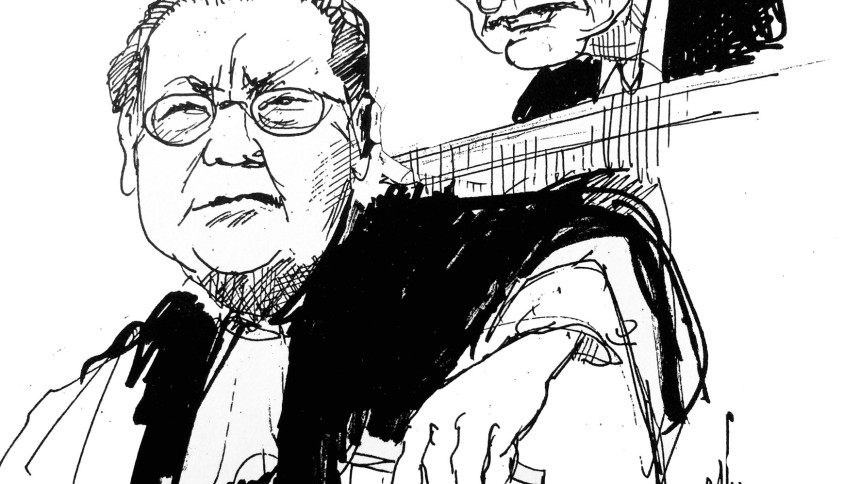

Trials and the judicial world are so closely linked to the history of cinema that they are a genre in their own right. From M (1931) to Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall) (2023), through La Vérité (The Truth) (1960), Procès de Jeanne d’Arc (The Trial of Joan of Arc) (1962), A Dry White Season (1989) and Il traditore (The Traitor) (2019), the courtroom has established itself as a favoured setting for the films. It has always fascinated filmmakers, raising questions of staging, and becoming the scene of intense drama where the truth of human beings is played out as much as the truth of facts.

Trials and the judicial world are so closely linked to the history of cinema that they are a genre in their own right. From M (1931) to Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall) (2023), through La Vérité (The Truth) (1960), Procès de Jeanne d’Arc (The Trial of Joan of Arc) (1962), A Dry White Season (1989) and Il traditore (The Traitor) (2019), the courtroom has established itself as a favoured setting for the films. It has always fascinated filmmakers, raising questions of staging, and becoming the scene of intense drama where the truth of human beings is played out as much as the truth of facts.

American cinema, in particular, is full of courtroom dramas, right up to the most recent works by William Friedkin (The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, 2023) and Clint Eastwood (Juror #2, 2024). These films borrow from the codes of thrillers and whodunits, revealing beneath the surface the hidden layers of a truth that is always in suspension. 12 Angry Men (1957), Sidney Lumet’s first feature film, offers an exemplary model: the doubt expressed by a lone juror becomes a discreet but powerful tribute to the democratic vitality of American institutions.

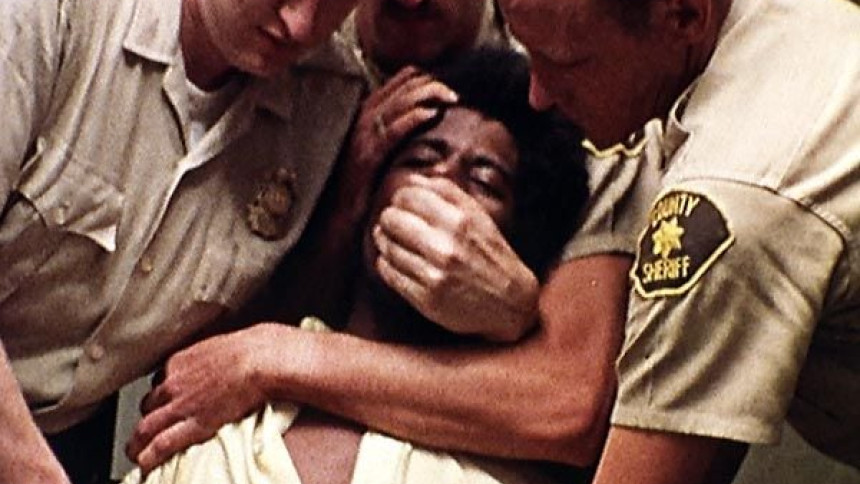

But the legal arena can also become a dark mirror of political excesses. In Punishment Park (1971), Peter Watkins’ dystopian work born out of the turmoil of the protest years (against the Vietnam War, the repression of minorities, and so on), trials are nothing more than Kafkaesque parodies, ringing out to the chilling echoes of the worst authoritarian regimes. From the 1950s to the 1970s, as America was undergoing a profound transformation, legal fiction captured the upheavals brought by this change.

Some films, such as A Dry White Season (1989), In the Name of the Father (1993) and Philadelphia (1993), are rooted in reality. They recount true stories and seek, through cinema, to heal the wounds of history. These trials become milestones of memory in tense political contexts – from apartheid South Africa through British-ruled Ireland to America grappling with the AIDS crisis. They offer a space for recognition and symbolic healing, and contribute to the social struggles that shake people’s consciences.

By its very nature, the courtroom is a place of eloquence, dramatic tension, and theatricality – but it is also fertile ground for fiction, ambiguity, and doubt. Three recent French films - Une intime conviction (Conviction) (2018), La Fille au bracelet (The Girl with the Bracelet) (2019), and Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall) (2023) - powerfully demonstrate this. All three reject the easy option of a clear-cut resolution, instead allowing confusion to emerge, questioning the characters’ morals, and inviting the viewer to become not only a witness, but also a juror.

Feature Films

That's not fair!

In partnership with Benshi

A short films programme for the whole family, recommended for ages 4 and up

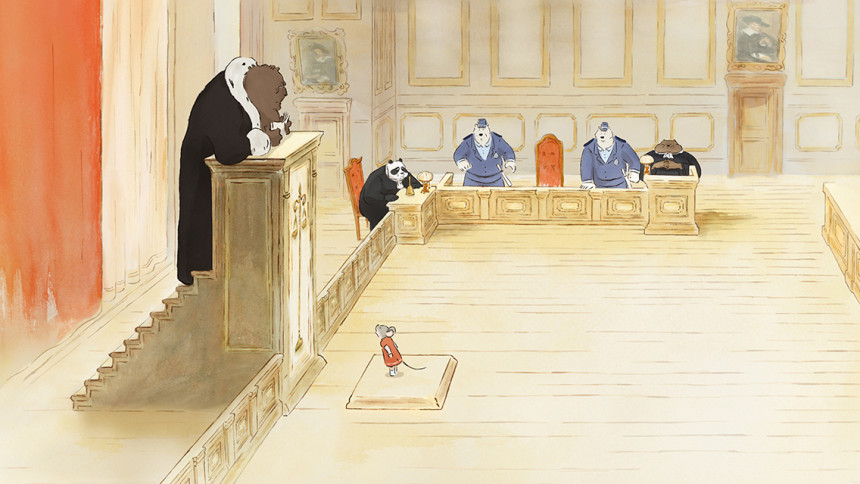

Why do some people have more than others? Why is life sometimes so... unfair? Through three poetic, funny, or mischievous short films, this programme invites children to explore the feeling of injustice that can be so revolting.

Benshi offers a unique selection of animated short films that give a voice to the little ones facing the big ones, the clever ones facing the powerful ones, the dreamers facing the norms. An invitation to reflect on the world around us, to question power relations and to believe in our ability to transform them.